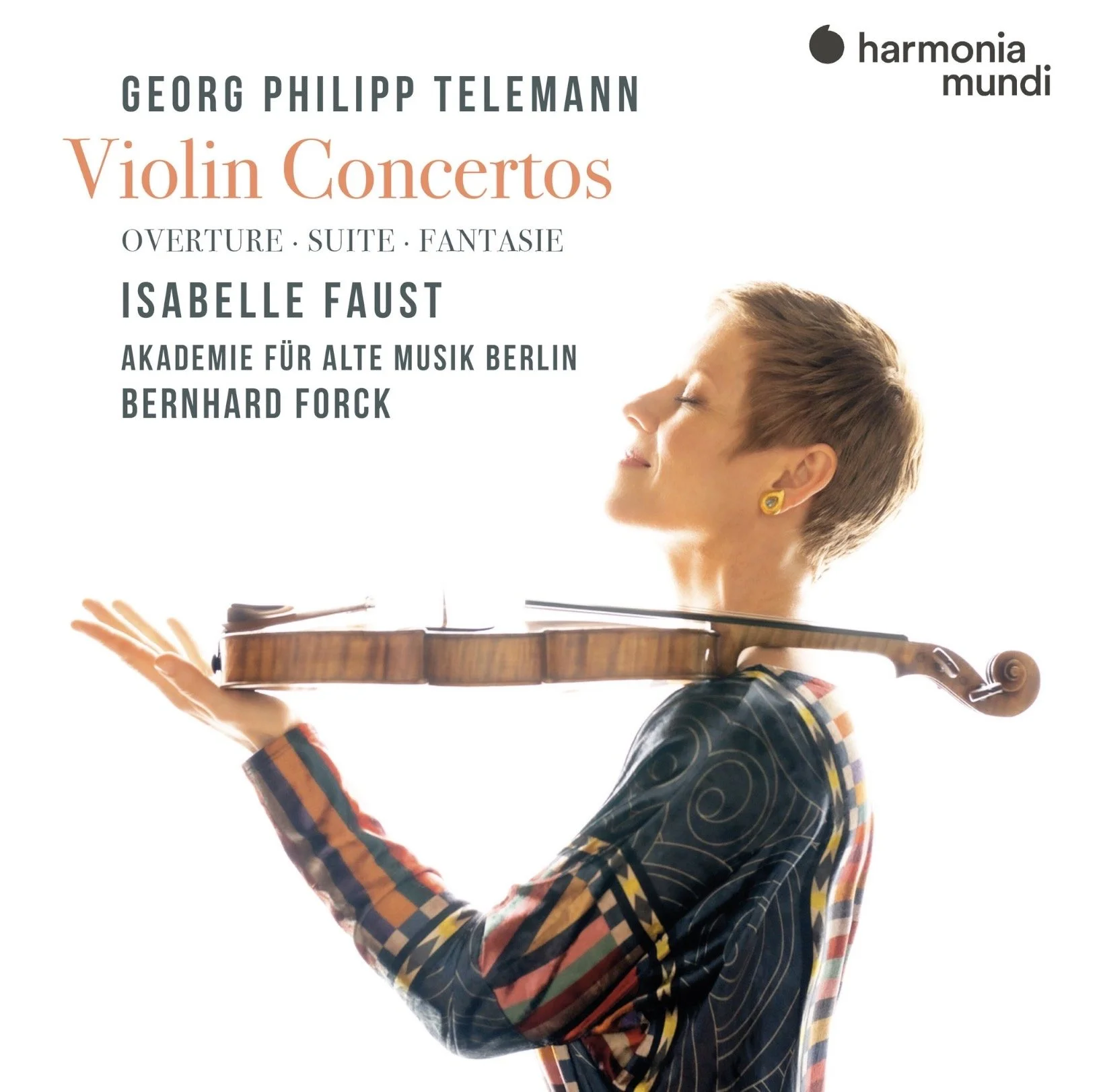

Faust • Works for Violin by Telemann

The title of this album is a bit of a tease. As was Harmonia Mundi’s pre-release of a track to whet our appetites. The album does offer two de facto violin concertos on offer, alongside other works, including a large, virtuosic suite in B minor, with solo parts.

The offering here, with all its variety, might just expose Telemann’s better side. I’ve found his concertos, and maybe it’s the concerto form, didn’t inspire the composer as much as others? It’s conjecture on anyone’s part to say, unless we have a smoking gun quote from the composer.

The album ends with a concerto that I felt has been a mainstay in my mind ever since I first heard it under the direction of Reinhard Goebel, appearing on a 1980s Archiv album of Telemann, the D major for violin and trumpet. The third movement offered the most lean and masculine sound that had come from MAK up to that point. The solo part Goebel contributed to my ears and sentiment was perfect.

Its inclusion here is fortunate, either in helping to connect Akamus to the past and familiar, or otherwise to offer us something superior?

The other pairing of trumpet and violin comes in the form of a sonata, the “Sonata spirituosa” that was also covered by MAK in their later years.

Also familiar to some, may be Telemann’s concerto named for an amphibian. The suite named after Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels is also included, giving Telemann fans enough familiar content to hang their preconceived notions at the door. (Or, said another way, welcoming them in with familiar fare, the same way diner offers us expectations for standards upon its menu.)

Unclear to me in this recording—which features a transparent sound with a wide, generous soundstage—is what kind of setup Faust is using. The booklet says she’s playing the Strad in this album, and not the baroque copy used in her recent recording of Bach sonatas.

————

Out of the gate, this album offers plenty of energy on tap, with tight, technically brilliant playing from all members of the orchestra and their guest soloist. The acoustic betrays the size of the ensemble, which comes across as especially generous. The recording kicks back in my room a little bit of bass bloom from the concert space, which helps contribute to the overall great sound of this album.

The tight playing and technical brilliance is captured all in one track, if you only had one to audition: listen to the final movement of the sonata for violin and trumpet, TWV 44:1. It had to be well-rehearsed, and the speed adopted all points to the brilliance of the musicians involved.

The Gulliver Suite, TWV 40:108 is something you should see, if you haven’t ever looked at the score. It’s impossible to appreciate the music in this case without seeing the lengths Telemann was willing to go to channel themes from its literary inspiration. My first exposure to this work came by way of Andrew Manze and Caroline Balding (also on Harmonia Mundi). This production feels another level more virtuosic in approach. Two players here—Faust and Forck—are well-matched in ability and sound.

I couldn’t help, however, but think that in this piece (as an example of what is also audible elsewhere across this album), that there is a level of polish and phrasing that goes beyond what Telemann left us in terms of paper and ink. The easy explanation is that there’s an attempt here to make his music come across more musical, wherein, the resulting sound isn’t what we’d expect, say, in a domestic environment.

The effect is brought forward with dynamics, with phrasing, and the exploitation of extra-musical effects with an emphatic wallop. Not to mention—making contrasting sections contrast to the tilt.

The violin fantasia TWV 40:4 presents Faust the opportunity in the nearly stylus-phantasticus style changing moods. I’m finding the emphasis on contrasts refreshing.

The A minor concerto, TWV 51:a1 might be a candidate for comparison, looking at Bach’s own A minor concerto. Wherein Bach’s inspiration for concertos seems clearly Italian, if not more specifically Vivaldian, Telemann championed 4-movement forms, beginning this concerto with a slow movement; allowing the soloist to emerge from the string texture. Faust does well to bring herself into focus in this first movement.

I became aware of this concerto through Standage’s early recording with Collegium Musicum 90. It may have also been featured by Manze, with his collaboration with a German ensemble. Standage—after his years with the English Concert—was a reliable interpreter, but his direction always for me held onto the “British HIPP” sound cultivated in the 1980s. By the time we get to Faust’s final movement of the same concerto, we can’t help but be confronted with the storm from the outdoors that’s extinguished the candles and blown all the music onto the floor. I appreciate the interest in trying to help us hear the music’s reason for being. The effect is in fact more virtuosic and for those who recognize these pieces as I do, the freshness is palpable.

To the aforementioned D major concerto for violin and trumpet that ends this recording, Faust and Goebel approach it quite differently. I’d offer that Faust is elegant, with a desire to highlight the upper register of her instrument. Goebel’s violin, by contrast, has a less refined sound, but its timbre and character is more enjoyable. There’s a brightness to the Akamus recording that is thankfully missing in the MAK recording. The phrasing offered by Faust is intelligent in the middle movement, but with Goebel the sound is more direct, the phrasing less tailored, the effect to us as listeners, the music a bit more raw. Both musicians lean into the repeated notes, recognizing the intensity of sound. With Faust, she offers more vibrato, which in this case, I’d rather have less of.

Ute Hartwich is every bit superior here to Friedermann Immer, a significant figure in historical trumpeters, who is featured in the MAK recording. Faust’s handling of the final movement offers many opportunities for showcasing the violin’s voice, but her overall approach is far more dynamic and inclusive of more emotional undercurrents than Goebel’s approach. It’s equally well-done, but I can’t give in to accepting it better than Goebel’s recording.

Finally, the opening work, it might be a comparison for us to Bach’s own B-minor (or as it’s believed, an A-minor orchestral suite) work, BWV 1067. TWV 55:h4 has been recorded before as well, although it’s a piece I’m not familiar with. The long opening gives multiple opportunities for the violinist to come out and shine against the ensemble. The mood is far lighter and forward leaning compared to Bach’s style. Akamus doesn’t seem interested on over-doing the French elements in this opening Overture.

The Gavotte opens with palpable energy from the ensemble, then turns nearly dark when the solo violin comes in, losing a bit of that dance energy. I’m not bothered by this, as no one would have been dancing to this music. The way Faust pushes into the orchestral sound, blending in the Loure, I think is well done.

The fourth movement is a study in articulation; the reading by Musica Alta Ripa manages to not lose so much of the opening momentum in the violin solo appearing in the Rejouissance. The rendering by Faust is far more detailed, but I that delicacy isn’t really missed in the earlier recording.

The approach she takes with La Bravoure, a dance I’ll admit is new to me, recovers from the disappointment in the earlier track; I’m less sure about her nearly going sul ponticello at one point, but if it’s not already apparent, she’s interested in color, affect, and maybe, surprises.

The finale, labeled Rodomontade , is a hustle-bustle type of energetic finale. Faust pulls out the stops again, going to play over her bridge in an icy display of virtuosity. Her performance in this movement isn’t in the same class as the aforementioned recording by MAR, Faust steps out front and dominates the stage, pushing hard to bring us clarity, technical assuredness, and musical variety.

Conclusion

There is thankfully since the 1980s many attempts to bring us Telemann’s wide and varied music–especially so his instrumental music—to audiences through recordings. The recordings by champions like Goebel, Michael Schneider, and Elizabeth Wallfisch are all important contributions, alongside others for sure.

Isabelle Faust is obviously a well-traveled and versatile soloist who takes baroque repertoire seriously. What I appreciated about this album is her willingness to not just “play along,” but to forge past what was done before and offer us a stylized view of Telemann’s music for violin in concertized settings.

The album offers us both the intimate, a solo fantasia and some duets, alongside an orchestral suite and concertos, proper.

While I am not willing to say she wiped the floor and outdid all previous attempts to showcase Telemann’s virtuosic vision for the violin, there’s much here to admire. I did not like the approach to the “Frog/s” concerto, thinking the programmatic indulgence went a bit far. That aside, however, even though Faust brings a lot of what I would consider her own voice and sense of refinement to this music, she did well to present a revised voice for Telemann. At least for me.

And her partners in Akamus were there to support her fully. Great collaboration.