Bach, Telemann, Albinoni: Concertos and Suites • Ensemble Masques

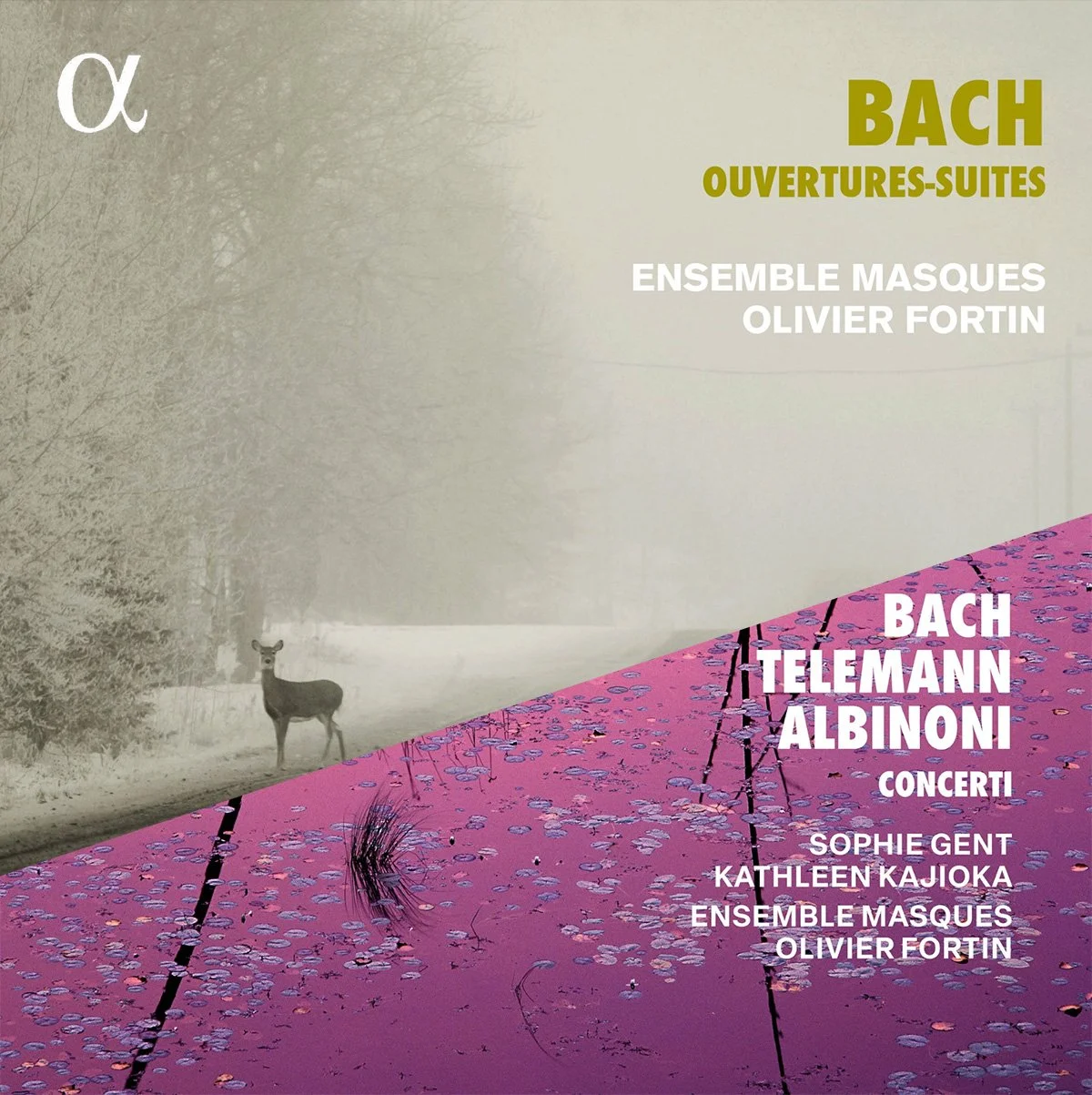

Concerti – Bach, Telemann, Albinoni

Introduction

This recording (July 2025), just over an hour long, would make an excellent concert program: Bach’s well-known violin concertos alongside Telemann’s viola concerto, two string concertos by Albinoni (mercifully not the famous oboe slow movement), and a brief Leclair piece from Op. 2 that might well have served as an encore.

A few decades ago, Baroque ensembles tended to record complete “collections.” If Bach wrote six partitas, you recorded all six. Vivaldi’s conveniently published sets encouraged the same approach. That practice hasn’t disappeared, but it’s less common. When familiar works like the Bach concertos appear on a new release, the question naturally becomes: what does this version offer that others do not?

Soloists Sophie Gent (violin) and Kathleen Kajioka (viola), both Masques regulars, perform alongside a very small ensemble: two ripieno violins, viola, cello, contrabass, and harpsichord. This reflects another modern trend—one-per-part concerto recording. When Monica Huggett did this with Ensemble Sonnerie, it felt novel; now it’s almost standard.

Historically, ensemble size was often dictated by practical realities. Larger HIP ensembles of the 1980s might use eight violins, multiple violas and cellos, and bass. Smaller forces, as here, offer a different advantage: transparency. Every gesture is exposed, and dynamics can feel more immediate—even if the recording slightly enhances their impact.

The Music

Bach’s Violin Concerto in A minor (BWV 1041) benefits from well-judged tempos, especially in the middle movement, which moves more purposefully than usual. Gent plays with excellent articulation and dynamic nuance, and the balance with the ensemble feels ideal.

Albinoni’s two Op. 2 pieces (Nos. 1 and 6) remind us that he wrote far more than oboe music. These chamber concertos for violin and two violas are handled confidently. Gent leads with authority, and the ensemble supports her with solid, stylish playing.

Telemann’s Viola Concerto in G major has become a favorite, given the number of performances. Kajioka’s tone is attractive, but the opening movement feels slightly slow—Masques takes 3:40, compared with Antoine Tamestit’s brisker reading under three minutes. The faster movements fare better.

The ensemble introduces a consistent rubato effect in the second movement. In live performance, visual coordination might enhance this flexibility; here, without that visual component, the effect feels less persuasive. Kajioka’s subtle embellishments in the third movement are welcome, and I would have enjoyed even more. The final movement’s pauses mostly work, though one extended hesitation slightly disrupts momentum. Still, the playing remains precise, and Kajioka’s tone is consistently appealing.

The album closes with Bach’s E major Concerto (BWV 1042). Gent brings welcome independence to her phrasing, using articulation and slight rhythmic freedom to energize the dialogue. In the first-movement hook near the end—an obvious invitation for improvisation—she, like most violinists, declines to add a cadenza. It’s a missed opportunity, though hardly unusual. Gent does differentiate by slowing this short solo interlude by Bach down, which does set this performance apart.

Conclusion

The final movement of BWV 1042 is exhilarating—among the most exciting versions I’ve heard. Gent’s performances alone justify acquiring this recording.

I am less persuaded by the Telemann, though I appreciate the ensemble’s willingness to experiment. Such interpretive risks can add freshness, even if not entirely successful.

The Albinoni and Leclair works provide effective contrast, even if they are not the primary draw. Fortin’s thoughtful programming—framing Telemann with related keys of G—shows careful planning.

Despite the skeletal forces, the recording never feels underpowered. Transparency, rather than weight, defines its appeal.

Bach: Orchestral Suites I–IV

Introduction

Released earlier, in June 2022, this recording adopts the same one-per-part approach. Suite No. 2 appears in its oboe version rather than flute, and Suites Nos. 3-4 omit the trumpets (and timpani).

Suite No. 1, BWV 1066

The scoring pairs oboes and bassoon with strings and continuo in constantly shifting combinations. Tempos are well judged, keeping the music moving—even in the menuets, which can sometimes drag. Dynamic contrasts, particularly in the Bourées, are effective.

Suite No. 2, BWV 1067

Lidewei de Sterck is the oboe soloist. Compared with the more familiar flute version, this scoring feels well suited to the smaller ensemble. Given that I recently heard the flute version, it can be difficiult to hear and the choice of an oboe may well have been a pragmatic one for Bach. Sterck's playing is poised, with an attractive tone and strong phrasing.

Suite No. 3, BWV 1068

Presented without later wind additions, this version emphasizes string clarity. Gent shines in the opening movement. The fast string passages are especially striking in their intensity and precision.

The famous Air is played without exaggeration, at what I consider an ideal tempo.

Suite No. 4, BWV 1069

Here, I missed the trumpets and timpani more than I missed winds in Suite No. 3. Their absence slightly reduces the music’s grandeur, particularly in the opening. Still, the Réjouissance works well in this configuration, taken at an energetic tempo and played tightly.

Conclusion

These “early” or chamber versions are not unprecedented, but Ensemble Masques performs them with exceptional polish and sensitivity.

The recorded sound maintains some distance, using the Poitiers acoustic to add weight. Balance is generally effective, though in live performance the winds might dominate more strongly.

Hearing these suites in such transparent form offers valuable perspective. The Third Suite, especially, is a revelation in this lighter scoring.

Taken as a Pair

These albums share a commitment to one-per-part performance and feature Olivier Fortin’s thoughtful leadership. His harpsichord playing adds welcome bite, and his tempos are consistently well judged.

The Orchestral Suites disc is the more satisfying overall, perhaps because I have a bias for Bach over other composers?

The recording approach favors spacious sound, occasionally at the expense of immediacy. I remain curious how a closer, drier recording might have changed the experience.

If you’re up for comparing the performance of the pieces by Bach, the 2011 recording by Freiburger Barorchester (Harmonia Mundi) makes an idea foil to the Overtures disc here by Ensemble Masques. Likewise, their 2013 recording of Bach’s violin concertos, which was so well done, is another excellent contrast. In both cases, both ensembles are on top form. FB offer a larger ensemble, with a fuller string complement, and the suites offer the bells and whistles with timpani and trumpets.

For my money, I want both. And those looking for a Telemann viola concerto without the hangups I mentioned that bothered me, the 2017 recording by Arion Baroque, another Canadian orchestra, offers for me a strong interpretation with soloist Jean Louis Blouin.