Bach: The world of the harpsichord • Gordis

Lilian Gordis is a Franco-American harpsichordist who left California at 16 to study with Pierre Hantaï in France. Her previous Bach album on Paraty combined two partitas, two English suites, and selections from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II. This new release focuses on the Sixth Partita—my favorite, largely for its opening Toccata—and the Sixth English Suite in D minor, again played on her Philippe Humeau harpsichord.

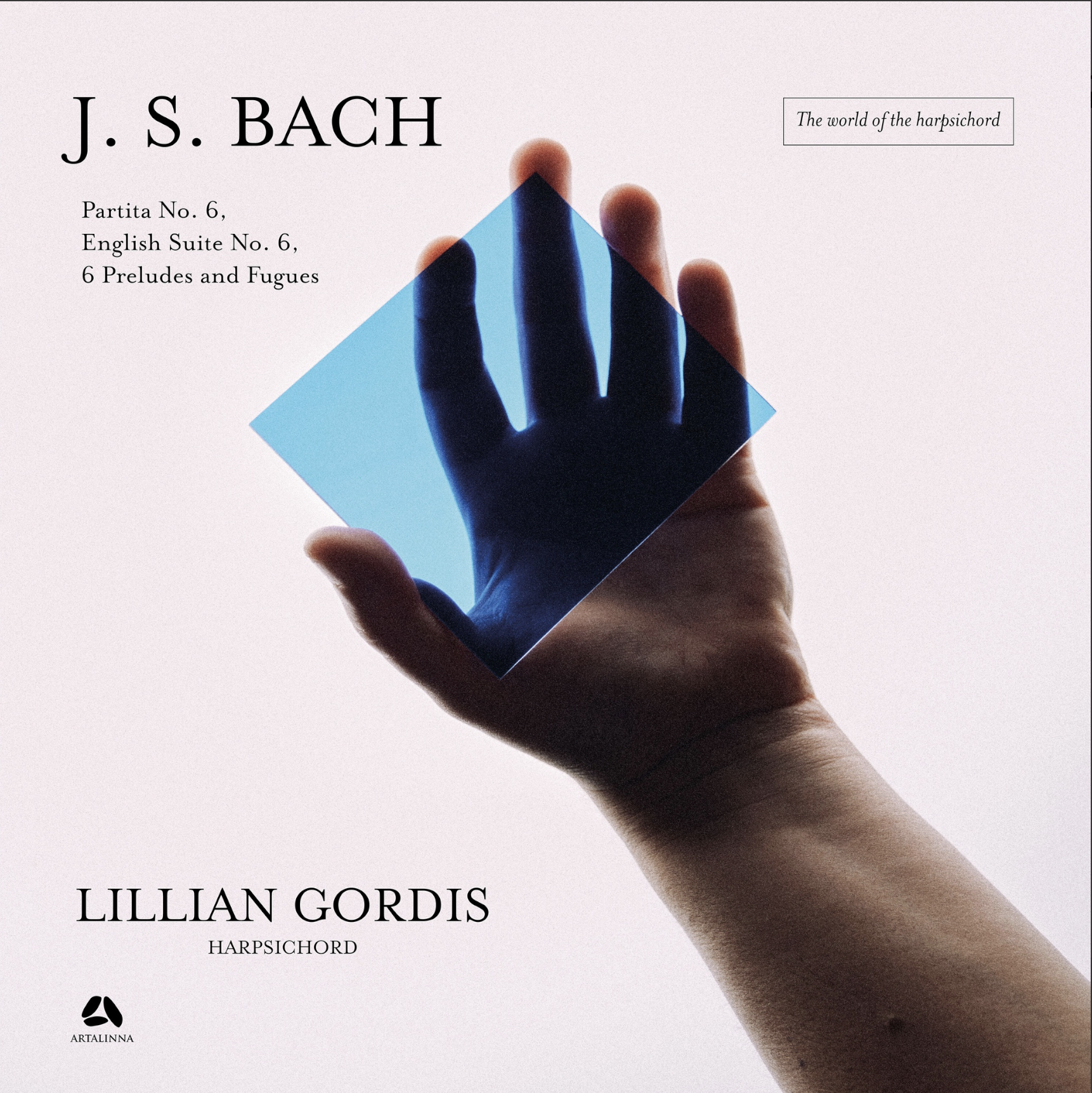

The liner notes are unusually personal, framed as a “prelude” addressed directly to the listener. Rather than offering conventional analysis, Gordis chronicles her life with this music and the challenges it has posed. I read these notes carefully and found their vulnerability refreshing—something rarer, and more engaging, than the typical academic essay. She also discusses the Mennonite church in Haarlem used for the recording, a space associated with Leonhardt and Hantaï. The resulting production is, in every sense, beautifully presented.

The two larger suites

The opening Prelude of BWV 811 immediately establishes Gordis’ interpretive stance. Christophe Rousset’s 2003 recording runs nearly two minutes shorter, propelled by his famously metronomic sense of time. Gordis, by contrast, allows herself to linger, shaping the music through rubato. Where Rousset forges ahead, she responds to the resonance of both instrument and space. Faster tempos would sacrifice clarity here; her choice feels right for both mood and acoustics.

A comparison with Benjamin Alard reinforces this point. Alard tends to push the pulse, yet in Gordis’ Allemande the dance feels exactly right, the melodic lead answered naturally by the left hand. Subtle rubato lets us feel the contour of Bach’s line rather than simply track its meter.

Her approach becomes more pronounced in the Sarabande. Some may find it mannered, but I would argue otherwise. Placed on a continuum between strict metronomic control and self-indulgent freedom, Gordis remains well within expressive good taste. The final suspended note left me hanging—deliberately, I think—as if asking whether we were truly listening.

The Gigue closes the suite with one of Bach’s many tours de force. Gordis does not launch headlong; instead, she gradually winds up the tension. A left-hand trill briefly brought Martha Argerich to mind for its sheer strength. I did miss, at moments, the raw drive of Alard, but Gordis compensates with transparency, at times rivaling—and occasionally surpassing—Masaaki Suzuki. Compared with Suzuki, she brings more sheer velocity. The result is invigorating.

We know little of what Bach thought about his own music, though we do know he looked backward often, studying earlier composers. That he paid to publish the keyboard partitas himself has led scholars to view them as especially significant, though this may run counter to Bach’s habit of continual revision—works were rarely “finished” in his mind.

As a set, the six partitas are heavyweight achievements. Even had Bach left us nothing else, they alone would mark him as a towering musical intellect. The Sixth Partita (BWV 830) opens and closes with the same dramatic material—passagework meant, historically, to wake the fingers—surrounding a central fugal section with a sighing, unforgettable theme. Gordis’ long relationship with this piece is immediately apparent; her interpretation feels more personal than many we hear today.

Her articulation in the opening and closing sections emphasizes repeated notes, and her rubato seems guided by the instrument’s resonance in the space. I did notice a brief timing hiccup around 3:46–3:56—intentional or an editing artifact, I couldn’t tell—which slightly disrupted an otherwise deeply rewarding performance.

The Allemande mirrors her approach in the English Suite. The Corrente, however, may suffer slightly from excessive rubato; here I longed for a firmer pulse. The same is true of the brief Air before the Sarabande.

That Sarabande, though, is one of the disc’s high points. It made me think of entering warm water—first enveloped, then watching ripples spread. Whether or not others share the image, Gordis’ rubato works beautifully here. The texture of the writing, the articulation of chords, and the harpsichord’s sonority combine into something nearly sensual, baroque in its indulgence, perfectly suited to a gilded room.

The Gavotte struck me as another place where a stricter pulse—à la Rousset—might have served the music better.

Bach’s genius in the opening of this suite is nearly matched in the Gigue, with its oddly searching theme and stabilizing countersubject. Rhythm is crucial here, and while Gordis does not abandon rubato entirely, she wisely maintains forward motion. The result preserves both coherence and character.

The preludes and fugues

The F-major pair (BWV 880) is well judged throughout. The prelude’s perpetual motion flows naturally, and the fugue benefits from gentle rubato, especially where Bach introduces a pedal point that allows the instrument’s resonance to bloom.

The A-flat major fugue (BWV 886) begins a touch slowly, but Bach’s harmonization is full of surprises, and Gordis’ tempo ultimately helps us acclimate to these unexpected landings. The effect is kaleidoscopic. Faster performances exist, but in this acoustic, her pacing—and a brief rubato near the close—feels justified.

The C-minor pair (BWV 871), one of my favorites from Book II, again departs from metronomic norms. The fugue exploits dissonance and resonance beautifully, and the church acoustic supports her choices well.

The G-sharp minor prelude surprised me with its brisk tempo, which I welcomed. I don’t know the temperament used, but this key sounds especially pungent here. The fugue, taken at nearly five and a half minutes (Pinnock manages three), challenges my patience. Its wandering subject gains coherence only against the countersubject; the advantage of Gordis’ tempo is the chance to linger in the color of the key, which pays dividends given her tuning.

The B-major fugue (BWV 892), with its organ-like character, again felt overly drawn out. Revisiting Friedrich Gulda’s amplified clavichord performance reminded me how celebratory this music can feel at a quicker pace. Gordis’ slower harmonic rhythm dampens that effect.

Conclusions

I didn’t love every choice on this double album, but that’s hardly unusual. The sound of her instrument and the recording itself are standouts, as is Gordis’ consistent and thoughtful use of rubato to shape Bach’s phrases. Rubato is often most effective when contrasted with its absence, but when applied with taste—as it largely is here—it almost always benefits the listener.

What I admired most is that Gordis clearly has something to say. As she notes in her liner comments, what she says today may differ tomorrow; a recording is only a snapshot. I’m invigorated by a performer unwilling to deliver the same reading repeatedly. Many of her tempo choices seem responsive to the church acoustic, intelligently balancing clarity, dissonance, and resolution.

Too often, recordings feel constrained by an imagined panel of judges enforcing a single “correct” approach. Here, I heard an artist with a freer spirit—one who invites us to admire Bach’s beauty through an organic, human performance that lets the player emerge distinctly from the notes. Gordis’ personality comes through, and in many moments it illuminates Bach’s genius.

This album has sparked my desire to revisit her earlier Bach recital and finally explore her Scarlatti recording. It should feel refreshing to many listeners.