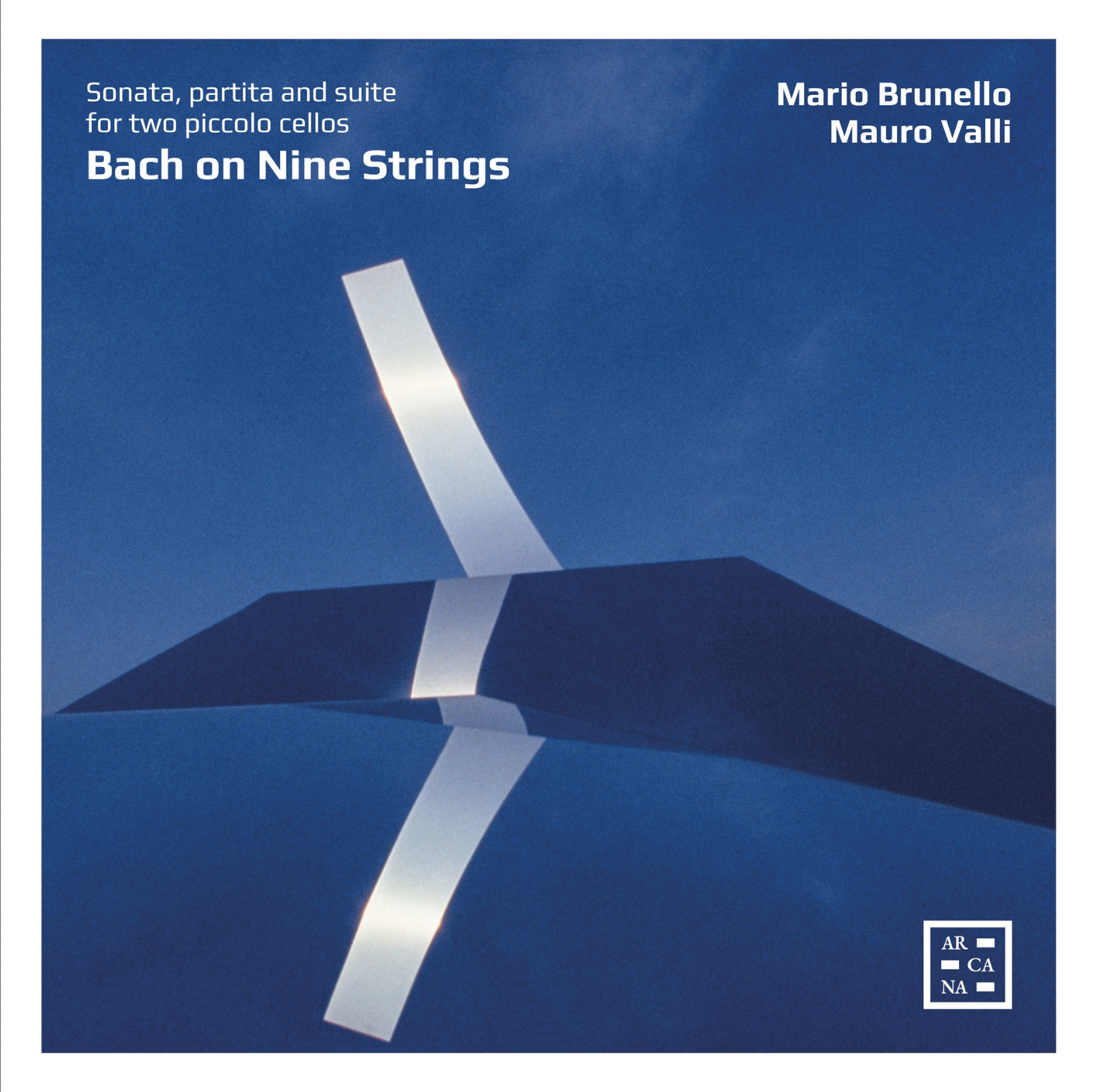

Bach on Nine Strings • Brunello & Valli

The starting point for this album comes from an interesting source: the transcriptions by Gustav Leonhardt of Bach’s violin works for keyboard. Someone involved in this process and specifically Leonhardt’s performances has been Skip Sempé, who contributes here a portion of the liner notes to provide context.

Except this is not a keyboard album but instead the collaboration of two cellists. Specifically, they’re playing violoncelli piccoli, one with four strings and the other with five, hence the title of the album.

There is some conjecture about what Bach meant by the small cello when it’s called for in his cantatas. Recent advocacy by artists such as Sigiswald Kuijken have advocated for the use of a violoncello di spalla, and there’s evidence that these solo parts would have been played by the violinist (as, Kuijken, a violinist, has done). I’m less convinced this was the instrument intended for Bach’s sixth cello suite, wherein the 5-string instrument used in this recording is probably what was envisioned. While the fifth string offers to extend the range of the regular cello northward, it here provides the bass support.

The album covers three works by Bach and they include the violin sonata BWV 1005, the third partita, BWV 1006, and the cello suite in C minor, BWV 1011. The resulting performances are done as arrangements, pulling apart the the originals and re-presenting them as duets. There’s a part of us that will want to hear these works coming from one instrument but when you find two musicians who seem to breathe in sync, listening to one another as they play, we just may be tricked into thinking there is a singular voice here, despite the rich stereo presentation of the music.

Mauro Valli:

I first met Mario in 1979. He was 19 and I was 23, and we were both competing in the ‘Città di Vittorio Veneto’ violin competition, which in that year also included the category of cello. After that, our artistic paths completely diverged. Although we remained united in friendship and mutual esteem for almost 50 years, we never had the opportunity to make music together. At last, fate saw fit to fill this lacuna, thanks to two passions we had in common: the sublime Bach and the violoncello piccolo.

I’ve not always been impressed—wholly impressed—by performances of Bach’s string works on the opposing instrument, cello playing violin, and violin playing cello. It can work, but the original, I think, always comes across as superior. In this case I think the arrangements offer us something compelling. I can’t think of a reason that admirers of these works wouldn’t find something of high value in this production.

The Fugue from BWV 1005 is a case in point: there’s something to be said about voicing multiple parts across two instruments, where we’re not held back by having to arpeggiate the chords but instead hear them a bit more upfront with all the tones sustained. At around eight minutes in, the two instruments trade runs back and forth, further accentuating the independence of the two voices within the fugue’s texture. I am not sure there is a clear analogue on the keyboard, unless one were to use two keyboards upon an organ or harpsichord to vary the timbre of voices.

The same track provides us another benefit: the delicious sonority of both cellos. This is a far cry from the sound of say, Rostropovich’s steel-strung cello. There’s an almost singing quality that comes from these instruments, enhanced by their phrasing and bowing together.

The roles in the same work’s Largo are more cut and dry: melody and bass. Bach’s writing in the original is interesting for combining melodic material with the sensation of a second independent voice, but here with that freedom, the melody takes on a new character. Playing more inwardly in this movement, the five-stringed instrument takes on a different timbre, one that is enhanced by a bit of vibrato which I think is done very tastefully.

The division of parts is less equal in the finale, marked Allegro assai. But even though the upper voice gets the bigger workout, they do manage to make the result convincing. There’s an opportunity perhaps lost in the repeats for not dividing the labor differently, but even as conceptualized, the energy and immediacy of the music comes off successfully.

The cello suite is among Bach’s darkest, and for me requires a different sound than what we got in the opening violin sonata. The Allemande takes on new life split between two cellos. I don’t know if the independence allows these musicians to give the movement a more dance-like feel, but that’s precisely what I take from it. I’ve never heard this movement feel more like a performance between two people moving about within a room. Yo-Yo Ma attempted this years ago with his Cello Suites films he made, performing each suite with a specialist in a different art form, using a dancer for one of the suites. But this recording nails the feeling for me.

One of the neatest dances from the cello suites is the fifth’s Courante. Such energy! These two musicians hold back that energy, I feel, offering us a very different feeling, it’s more tempered, more a dance than an aggressive outlay of human frustration. The independence of a melody with the support of the bass line works so well. It’s here, again, that the stereo separation of the two musicians works equally well on headphones as it does mixed together a bit more through speakers.

The choice to play pizzicato in the opening of each half of the Sarabande was an interesting choice. It works well I think in helping us hear each instrument in space, and I like that they start and end plucking.

The Gigue, like the Allemande, feels again like a dance between two people. Remarkable how this performance messes with your mind, recalling the original played by one instrument. This is both novel and satisfying. It feels right. I also like that they took their time with this one; it would have been too slow played by a single player, but this tempo works.

The most recognized part of the violin partita is the opening, for which Bach himself reused. I don’t how anyone couldn’t hear this opening track and not have a smile plastered across their face. Ah, the power of music! Between the two instruments there’s a very gritty, palpable feeling of pulse that comes out that often I’d think a violinist would try and hide, to smooth out? But I love it when they’re locked in, digging in, the sound of two bows pulling out those notes in tandem? So satisfying it is to hear. I had to fight myself not to turn up the volume dial.

There’s that same tactile quality that comes out in the Gavotte en rondeau. Which showcases for us that simply employing two instruments isn’t going to result in this kind of musical result, it takes musicians who can each get into their sound and consider how it will work with their partner. I’m in love with the four-stringed instrument’s sound.

The drone effect in the second Menuet is sublime. The Gigue works well as two independent parts, a bit different from the cello suite’s gigue. I wanted the five-string instrument playing the bass role to come out a bit more, played by Valli.

Conclusion

This album is gorgeous. Recorded in the Teatro Sant’Agata Feltria near Rimini, there’s credit deserved by this acoustic space and engineer Michael Seberich. It is somewhat sad that these two musicians waited so long to collaborate; but this album thankfully came out of both friendship and shared admiration for the music. I can’t say I’ve ever heard an album that comes across more true to those guiding impulses.