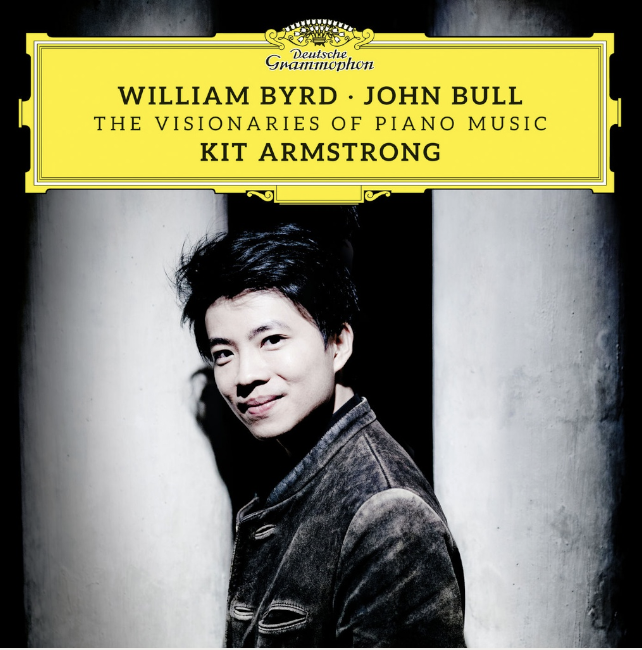

Visionaries of Piano Music: Byrd & Bull • Armstrong

Introduction

There’s a knee-jerk reaction to the title of this album. Of course William Byrd and John Bull never knew or experienced a concert grand. From a HIPP perspective, it would be easy enough to write this performance off as ill-conceived if we insisted on approaching this music strictly from its point of origin as repertoire intended for virginals—music meant as much for the enlightenment of the performer as for a potential audience.

William Byrd (c.1540–1623) was the most important English composer of the late Renaissance. A master of vocal polyphony and keyboard writing, he served the Chapel Royal under Elizabeth I while remaining a committed Catholic. His keyboard works—grounds, fantasias, and dance forms—combine contrapuntal rigor with expressive freedom and stand at the foundation of the English virginal tradition.

Doctor John Bull (c.1562–1628) was one of the most virtuosic keyboard composers of his generation, receiving his terminal degree from Oxford. A contemporary of Byrd, he pushed technical boundaries with brilliant figuration, rhythmic complexity, and daring harmonic turns. His career was marked by controversy and exile, but his keyboard music remains among the most imaginative and technically demanding of the English Renaissance.

To be sure, I revisited the important recording of Byrd’s complete keyboard works recorded some years ago on Hyperion by Davitt Moroney, which I’ve often thought of as an authoritative reference. The historical instruments he chose for that set have such a profound character of their own that it’s difficult to imagine the music divorced from early keyboards altogether.

Yet the performer here, Kit Armstrong, has suggested—cheekily, in one of his videos exploring historical keyboards—that the modern piano is an instrument upon which we can play all periods of music. It’s a profound statement in its simplicity, even if we remain aligned with wanting to hear this repertoire on instruments contemporaneous with its creation. After hearing Armstrong’s most excellent performance of Mozart’s Alla turca on a period Walter piano, I found myself drawn into his musicianship, despite having paid little attention to him previously.

It’s funny how I came upon him, thanks entirely to the internet. I’d started my day watching a video of the Franco-Chinese pianist Xiao-mei Zhu and, following that thread, arrived at Armstrong. The pianist—who grew up outside Los Angeles—presents as something of a polymath: beginning piano at five, appearing on Letterman at ten, later pursuing advanced studies in mathematics and artificial intelligence. For over a decade he has owned a former church in France, where he concertizes with other musicians.

As for Byrd and Bull on the piano, Armstrong addresses this directly in his liner notes:

As much as the historical practice of the 18th century has been the subject of fruitful research, that of the 16th century does not engender comparable expectations, if only for a dearth of secondary literature. This, however, does not prevent me, faced with these amazing works, from doing what makes sense according to what I see in the music, enjoying the results thereof, and adapting my views whenever new knowledge or understanding may emerge. After all, is it not one of the time-honoured sources of rapture in the world to appreciate an artwork beyond how it was first designed to be appreciated?

Here, Armstrong asks permission to appreciate art beyond its original design. Framed this way, the argument is persuasive. Much of the art we encounter today—whether music or visual—was not created with concert halls or museums in mind. One might argue similarly about modern composers’ works performed on a Stradivari violin: the result could feel foreign to the maker, yet meaningful to the listener. Armstrong’s framing is more subtle still when he invokes “rapture,” reminding us that appreciation need not be singular or prescriptive.

This stance might feel scandalous if it weren’t already well established across repertories. Glenn Gould performed Bach—and even the virginalists—on the piano. Wendy Carlos reimagined Baroque music on the synthesizer. It took only a few tracks here to convince me to set aside my usual allegiance to historical performance practice.

Under Armstrong’s command, Byrd and Bull become visionaries. Of piano music.

Performances

Let’s start with Bull’s Fantasia (track 8). The droning repetition in the left hand, the fanciful, florid writing for the right—tell me this doesn’t evoke, at least fleetingly, a Keith Jarrett improvisation. Byrd’s Pavan and 2 Galliards (Earl of Salisbury, tracks 16–18) retain all their ornamentation but take on a markedly different character on the piano. Armstrong embraces equal temperament and the instrument’s timbre to recast these works. Open triads, in particular, sound almost modern within Byrd’s harmonic language.

The left hand in the two galliards stands out, especially given how prominently it’s featured, trills and all. The dynamics and projected mood are undeniably new. The effect is very different on piano—but honestly, it’s not a disaster. Not at all.

Bull’s Walsingham variations invite comparison with Bach’s Goldberg Variations. The tune itself is simple enough that one might doubt its capacity to sustain such elaboration. Bull proves otherwise, deploying nearly every compositional device at his disposal—especially rhythmic variation. With no performance markings for fingering or phrasing, much is left to the performer. Armstrong largely avoids repeats, playing the work through with only brief pauses between cadences, maintaining forward momentum. His control is exquisite, dynamic choices judicious, articulation finely judged—particularly striking in the twenty-eighth variation. Despite its complexity, he makes the piece sound effortless.

Armstrong includes both composers’ Walsingham settings. In a separate lecture-video, he discusses Byrd’s version, which appears here as track 30. While some of the described complexities may not immediately register, that opacity is part of the music’s charm. Byrd’s treatment begins more simply than Bull’s, growing steadily in complexity as four-part writing demands dexterity in both hands. Byrd competes with Bull not only rhythmically but harmonically. Armstrong’s technique never falters as textures thicken and note density increases.

I revisited Pieter-Jan Belder’s harpsichord performance of Byrd’s Walsingham, where the contrast lies not only in timbre but in tuning. Belder’s account strikes me as stronger than Moroney’s, though the piano inevitably tells a different story.

These examples represent only a portion of this double album. The repertoire can be challenging; it is learned music, deeply rooted in vocal practice. The limits of period instruments can sometimes constrain these ideas, though Armstrong remains faithful to the scores—these are not arrangements. Written at the close of the Renaissance, the pieces inhabit a modal harmonic world that feels kaleidoscopic, with rhythmic shifts constantly refracting familiar shapes.

Armstrong seems to treat each work as a self-contained micro-world. The art lies in how themes are worked contrapuntally, especially in the paired Walsingham variations and Bull’s canons (track 29). On the piano, some solutions feel foreign to later keyboard traditions, yet when heard through a twentieth-century lens, certain passages sound strikingly forward-looking.

There is little doubt that Byrd and Bull represent the culmination of an era. Visionary, perhaps—not by foresight, but by extracting the maximum expressive potential from their instruments. Their extended runs often feel closer to Liszt than Purcell. Armstrong somehow prevents these flourishes from sounding labored; his technique seems yoked directly to the composers’ imaginations.

On the piano, these ideas truly take flight. Armstrong clearly comes prepared, and while I will always return to historical instruments for this repertoire, this recital presents Byrd and Bull in a new and compelling light—one made possible by extreme, and sensitive, virtuosity.